Java: UnmodifiableList vs. ImmutableList vs. Array.copyOf

I’ve recently had a discussion about the way lists and other data structures are stored in memory, especially when it comes to references and their assignment. It turned out that deep and shallow copy raise questions, which for someone who comes from a C++ background (such as myself), have quite obvious answers. Before I switched to Java, I had to think whether I can safely iterate over a data structure created by a different object or I had to duplicate a part of it in the memory, before it gets swiped by the original owner. Java makes it less explicit what sort of memory ownership You have, therefore today I’d like to look under the hood to give You a simple, yet powerful understanding of the differences between an UnmodifibleList, ImmutableList and finally a thorough copy of it. Let’s dive in!

Something to work on

To demonstrate all of the examples we’ll start with a simple code snippet, which defines a simple class (let’s call it “A”) holding a String and int.

class A {

private String text;

private Integer number;

public A(String text, Integer number) {

this.text = text;

this.number = number;

}

public void setText(String text) {

this.text = text;

}

public void setNumber(Integer number) {

this.number = number;

}

public String getText() {

return text;

}

public Integer getNumber() {

return number;

}

}We’ll create a few objects of this type and put them in an ArrayList.

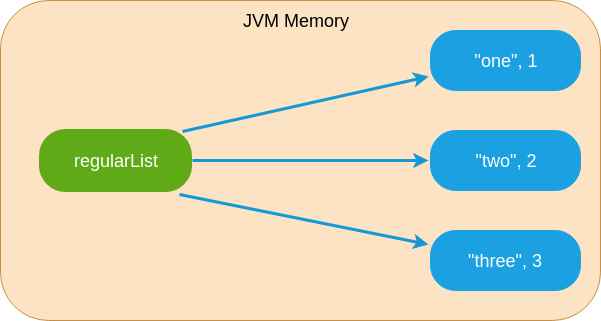

List<A> regularList = Stream.of(

new A("one", 1),

new A("two", 2),

new A("three", 3))

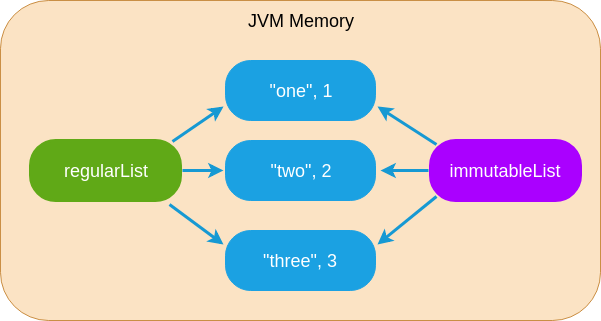

.collect(Collectors.toList());Our current solution would be represented in the memory in the following manner:

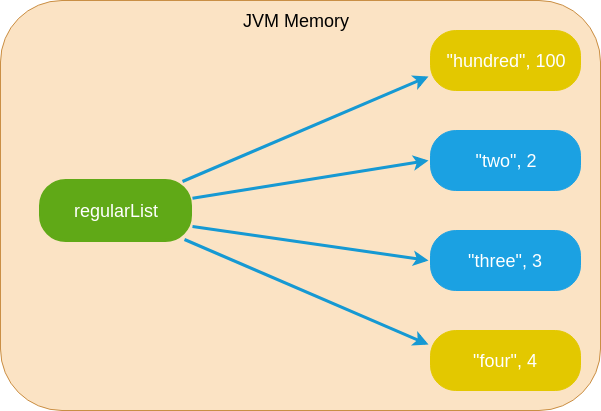

In the examples, which will follow in the rest of the article, we’ll be expanding the original list by adding one more element (“four”, 4) and modifying the first one (“one”, 1) –> (“hundred”, 100).

regularList.add(new A("four", 4));

regularList.get(0).setText("hundred");

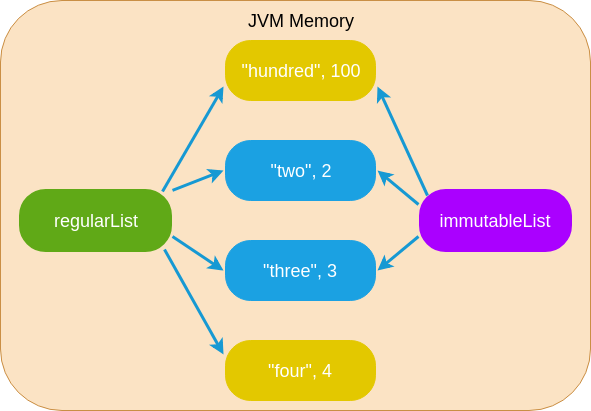

regularList.get(0).setNumber(100);The representation in the memory is shown below with the modified/added elements marked in yellow.

Now let’s delve into the methods providing different ways to protect the list from modification and how they differ from one another.

java.util.Collections.unmodifiableList

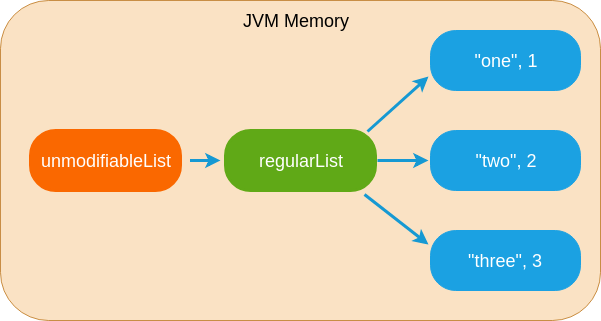

The Unmodifiable family from java.util.Collections are wrapper classes (often called views), which’s only purpose is making sure that no setter gets called on a certain data structure. An UnmodifiableList is just another object, which holds a reference to the original List.

List<A> unmodifiableList =

java.util.Collections.unmodifiableList(regularList);

Its interface makes sure that all methods, which don’t modify the list are passed through, while all the ones, which do, end up throwing an UnsupportedOperationException.

// this will pass, as the Collection interface setter functions for the UnmodifiableList such as add() are overloaded to throw in such case.

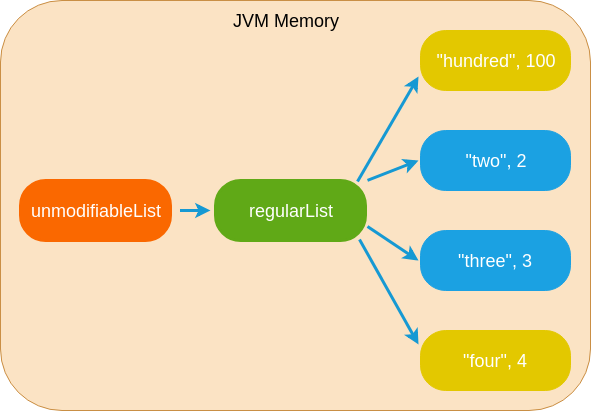

assertThatThrownBy(() -> unmodifiableList.add(new A("hundred", 100))).isInstanceOf(UnsupportedOperationException.class);Since the UnmodifiableList is just a view, this implies that any change in the original list will transpire to the unmodifiableList since it’s the same memory after all.

regularList.add(new A("four", 4));

regularList.get(0).setText("hundred");

regularList.get(0).setNumber(100);

// Check that it's a shallow copy, which means that both lists are referencing the same object

assertThat(unmodifiableList.get(0)).isSameAs(regularList.get(0))

assertThat(unmodifiableList.get(0).getNumber()).isEqualTo(100); // it is, since they unmodifiableList points to the same list as regularList

assertThat(unmodifiableList.size()).isEqualTo(4); // true for the same reasonThe UnmodifiableList is meant to be used in the getters, which expose the object’s List type fields, but by design are meant to be read-only. Care must be taken however, as if the list itself changes, so will the view, as mentioned earlier.

(Guava) com.google.common.collect.ImmutableList

We’ve already said that if an element is added to the original list, it will also show up in the view. There are however cases, when we would like to guarantee that the list of elements stays the same once passed to another object. This might be the case if, for example, we wanted to get a snapshot of a list of Tasks, which are in a queue. Since they are probably executed and then removed in a different thread, it might make sense to get a read-only list, which won’t change while we will be iterating it. To do that, we actually have to create a copy of the original one and populate it with the same elements. This is where the ImmutableList comes in handy.

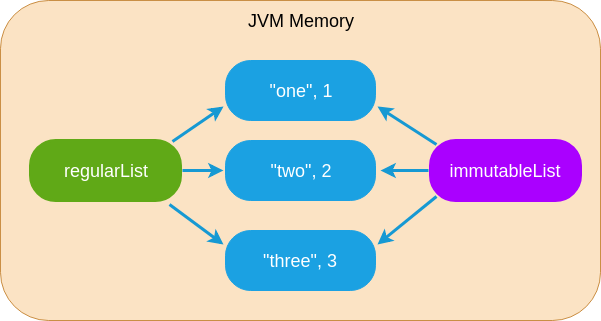

List<A> immutableList = ImmutableList.copyOf(regularList);Let’s look at the memory after this call.

As we can see, the immutableList object still points to the same elements as the regularList. This has a serious repercussion. While the immutableList won’t be impacted by adding or removing any elements from the regularList, if one of the elements changes, it will still “leak” to the premier one. Let’s apply the changes, which we made before and see the results.

regularList.add(new A("four", 4));

regularList.get(0).setText("hundred");

regularList.get(0).setNumber(100);

// Check that it's a shallow copy, which means that both lists are referencing the same object

assertThat(immutableList.get(0)).isSameAs(regularList.get(0));

assertThat(immutableList.get(0).getNumber()).isEqualTo(100); // same as with unmodifiableList - a different list object, but still references the same elements.

assertThat(immutableList.size()).isEqualTo(3); // notice that the immutableList didn't grow!

As we can see, adding an element to the regularList does not affect the immutableList, because it’s a separate object with its own references to the elements. However, since both lists make use of the same objects, if we modify the first element, it will also affect both of them.

Do mind that modifications of the immutableList through method calls were invalidated in the same manner as in the UnmodifiableList.

assertThatThrownBy(() -> immutableList.add(new A("hundred", 100))).isInstanceOf(UnsupportedOperationException.class); // throws the same exceptionIf we look inside the ImmutableList.java file, we’ll know that it’s the same solution as we’ve seen in the java.util.Collections package:

// Taken from Guava's ImmutableList.java file

/**

* Guaranteed to throw an exception and leave the list unmodified.

*

* @throws UnsupportedOperationException always

* @deprecated Unsupported operation.

*/

@Deprecated

@Override

public final void add(int index, E element) {

throw new UnsupportedOperationException();

}List copy

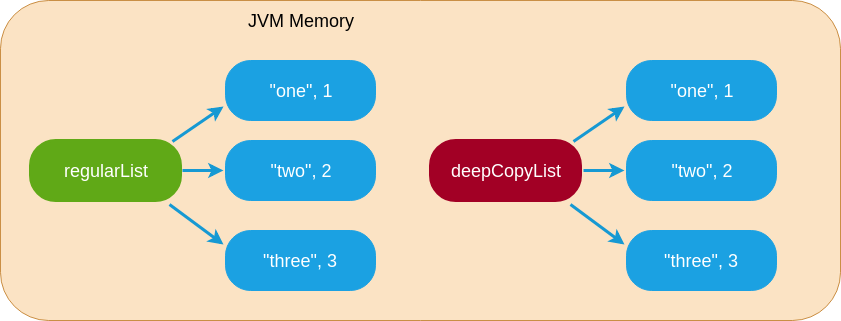

The previous methods were quite lean memory-wise. The UnmodifiableList is just a single reference, the ImmutableList requires a new list with all of the references, but still reuses the same objects lying underneath. If however we’d like to make sure that our list is not touched by anyone externally, we have to have our own copy for ourselves. This means not only duplicating the list itself, but also the elements it was pointing to.

List<A> deepCopy = new ArrayList<>();

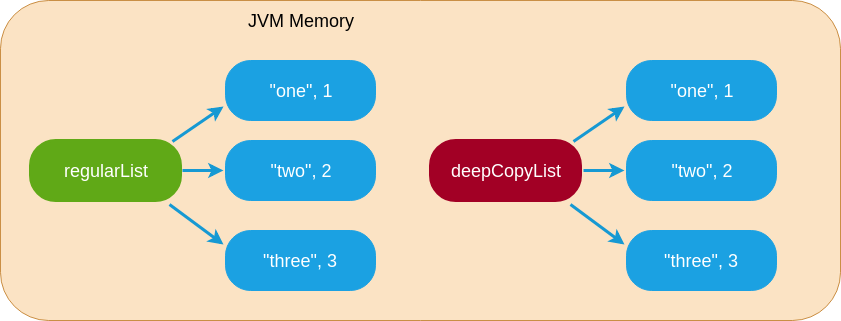

regularList.forEach((element) -> deepCopy.add(new A(element)));Let’s look at how this would look like in the memory. As we can see, there are separate objects holding the lists as well as we have copies of all of the elements (A class objects).

In the code presented above You could have noticed a copy constructor being used for the A class, which wasn’t defined before. To simplify the code in the lambda I used one and if You doubt how it was implemented - just for reference:

public class A {

// I've added this copy-constructor

public A(A element) {

this.text = element.text;

this.number = element.number;

}

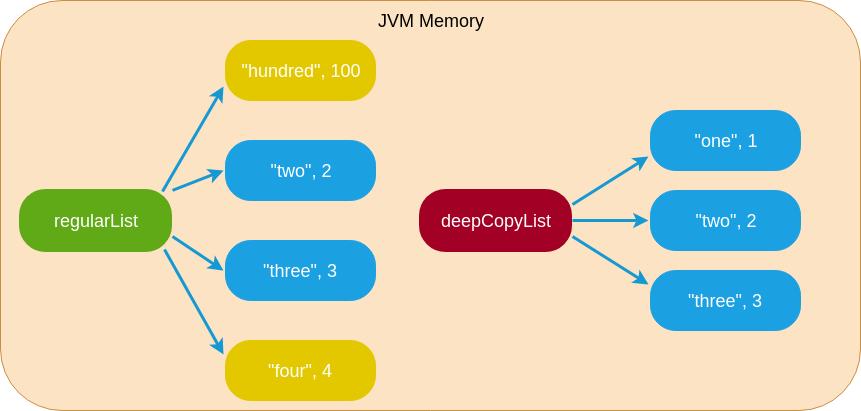

}After creating the copy of the regularList the deepCopyList is totally separate so modifications in the premier won’t affect the latter. Let’s check it:

// Check that it's a deep copy, which means that both lists have references to different objects

assertThat(deepCopy.get(0)).isNotSameAs(regularList.get(0));

assertThat(deepCopy.size()).isEqualTo(3);

regularList.add(new A("four", 4));

regularList.get(0).setText("hundred");

regularList.get(0).setNumber(100);

// Check that the deepCopyList was not affected by the modifications in the regularList

assertThat(regularList.get(0).getNumber()).isEqualTo(100);

assertThat(deepCopy.get(0).getNumber()).isEqualTo(1);

assertThat(deepCopy.size()).isEqualTo(3);All of the above tests pass, because each list is a separate one. Let’s look for the last time, how it looks like inside the memory after all of the changes were applied to the regularList.

The deep copy does guarantee that we get to own all of the data inside of the list as well, but as such requires the most resources.

Shallow Copy vs. Deep Copy

We’ve already seen the difference between the immutableList object and the deepCopyList. The first one was a shallow copy, while the second one was a deep one, as stated by the object name. In Java terms we can express it this way: A shallow copy would be cloning() the original object and copying the references to any objects it held. In result the references inside both objects (original and copy) would point to the same elements. In a deep copy, every object owned by the copied object would also be cloned() and a new reference to it created. Java generally discourages deep copying as it requires double the memory: if a list with elements took 1MB of RAM, after the deep copy is done, both objects would take up a total of 2MB. In a shallow copy, the overall cost is the size of the list object and the sum of memory taken by object references, which are just memory pointers (32 or 64-bit depending on the JVM version used).

Shallow copy - immutableList and regularList point to the same underlying objects

Shallow copy - immutableList and regularList point to the same underlying objects

Deep copy - every element referenced by regularList has been duplicated and attached to the deepCopyList as a totally separate object and new reference untied to the original object.

Deep copy - every element referenced by regularList has been duplicated and attached to the deepCopyList as a totally separate object and new reference untied to the original object.

Example code

All of the examples from this entry are available on my Github repository: Unmodifiable Lists on Github.

References

Tutorials Point: UnmodifiableList Baeldung: Immutable ArrayList in Java ImmutableList in Java 9